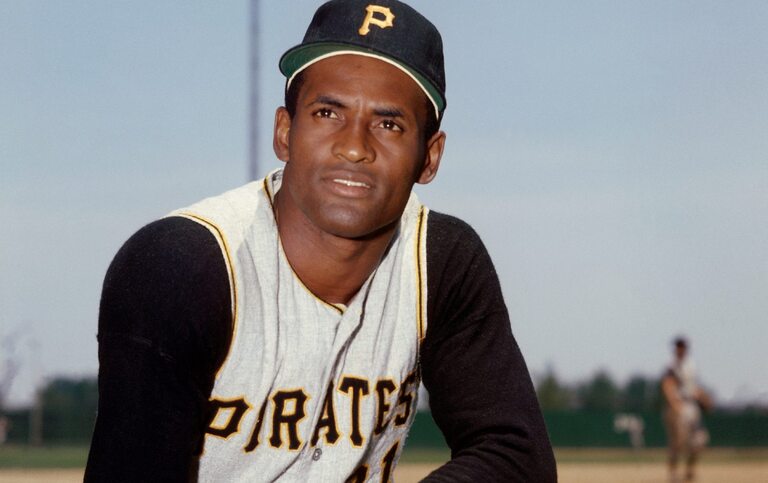

What Would Roberto Clemente Do?

Roberto Clemente. #21 of the Pittsburgh Pirates. poses for a photo in 1968. (Louis Requena / MLB via Getty Images)

The right fielder would want the baseball players’ union to fight the Trump administration’s campaign of terror against immigrants and their families.

The Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist David Maraniss says that he never speaks for the dead, but in this one case, he’ll make an exception. I had asked the best-selling author of Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero what baseball Hall of Famer and Latin American icon Roberto Clemente would say about Trump’s sadistic immigration policies and Major League Baseball’s silence in the face of these policies. Maraniss responded, “I have no doubt: Clemente would speak out on behalf of the many thousands of Latino jibaros and trabajadores who give so much to this country and are now living in fear of ICE shock troops. Clemente would be clearly denouncing Trump’s overtly racist policies.” Maraniss added that Puerto Rico’s favorite son would also be agitating for a league so dependent upon Latin American talent to stand up for its players.

Major League Baseball’s silence over (or perhaps silent support for) Trump’s denaturalization efforts would have been shattering for Clemente, because his era was one of progress. Clemente’s generation changed the complexion—and languages—of MLB clubhouses forever. When Clemente entered the league in 1954, he was one of the first Latino players with the dark skin tone that would have kept him out of the game before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. Clemente later said that he first learned about racism—and first learned about what it meant to be Black—upon entering Major League Baseball and coming to the US mainland. Clemente fervently supported the rising Black freedom struggle. Clemente entered a league with racial quotas, which on some teams was still zero. In 1972, he left as captain of a Pirates team that could field a lineup of African American and Afro Latino players, a team beloved in what was then a white, blue-collar town.

Today one can imagine Clemente, if somehow reanimated for the present, initially ebullient over the state of Major League Baseball. He would see a record six managers of Latino descent. He would hear his first language and music in the clubhouse, including the reggaetón of Puerto Rico’s own Bad Bunny. He would appreciate stars like Manny Machado and Julio Rodriguez. And then his heart would break to see the league refuse to defy Trump and protect these players and their families. Not even the ballpark, that place of escape and community connectivity, is a sanctuary. If anything, they are ICE target zones.

Mari Corugedo, vice president of the League of United Latin American Citizens, wrote me, “The fact that you can’t go to a favorite pastime of the United States, like a baseball game, without thinking in the back of your head, that someone in a mask, someone who won’t show you their badge or name, can come and separate and use this as a weapon against your parents, your family members, your friends, anyone who attends these sports events.”

If the NFL’s tagline is “Football Is Family,” MLB’s might as well be, “Baseball: Your family is not at present in an undisclosed location. Enjoy the game.”

Maraniss made another point about Clemente. “As a strong member of the players union,” Maraniss said, “he’d be pushing for them to take an unequivocal stand.”

Indeed, Clemente helped lead baseball’s first union strike in 1971 and was one of the few Major League Baseball players to defend fellow All-Star Curt Flood’s efforts in 1969 to win free agency for all baseball players. Clemente’s instincts to look to his union to fight Trumpism would have been spot-on. The Major League Baseball Player’s Association could be a uniquely powerful force against Trump’s anti-Latino assault.

This is a union where a quarter of its members were born in Latin America and many of the rest of its players are from comfortable suburban backgrounds and colleges with names like Gunnar, Colton, and Adley (to just use my favorite team as an example). What a statement to a divided country and a nativist president if this union of both Kades and Eduardos could publicly condemn the terror being imposed on their members. The players would become leaders giving voice to people who right now are living in shadows, deliberately unheard.

The Nation reached out to the MLBPA, but on this issue, it has been less deliberately unheard and more deliberately silent. “The PA is closely monitoring all U.S. immigration developments that could impact our members,” a representative of the MLBPA wrote. “We have advised non-U.S. citizen Players to carry proper immigration documentation with them when they travel and to ensure that their paperwork and personal information is up to date with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). We are available to Players and agents around the clock as a source of information and support, and we will remain attentive to any enforcement trends that could impact Players and their families.”

This echoes what Tony Clark, the executive director of the MLBPA, told the Baseball Writers Association of America during the All-Star break. The following was sent to us by the union, complete with vocalized pauses. After Clark made the same declaration of legal support, he said, “We told them to carry their documentation, uh, uh, wherever they go.… we’ve got immigration council and immigration lawyers on staff to provide, support in a way that we have in the past, but not to the extent that we do now in order to ensure guys are in the best position possible to get to the ballpark and do their job.”

There is no way this would be good enough for Clemente. Make sure you have your papers? Here is a number of a good lawyer? That doesn’t meet the moment. It accedes to it.

More columns ⇒

Support the Work

Please consider making a donation to keep this site going.

Featured Videos

Dave on Democracy Now!