The Late Pete Rose Is Finally Welcome in Baseball’s Moral Slophouse

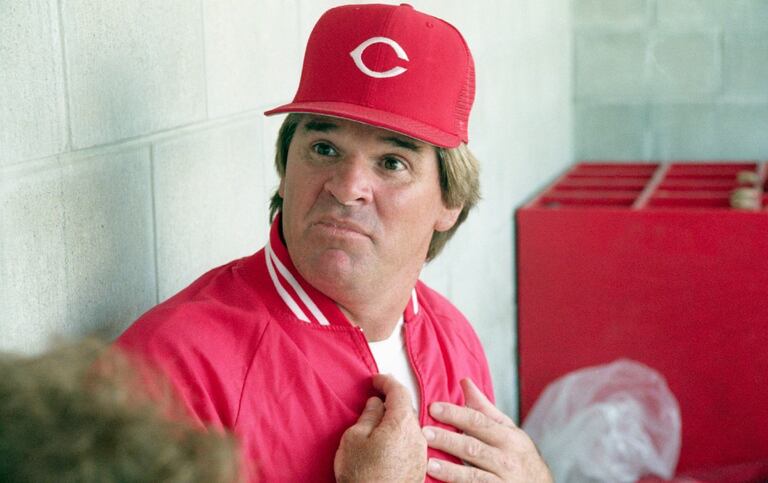

Cincinnati Reds manager Pete Rose reacts to a reporter’s question on March 22, 1989, prior to the Reds’ against the St. Louis Cardinals. (Bettman via Getty Images)

Joe Jackson and Pete Rose will no longer be banned from the Baseball Hall of Fame. The decision is likely rooted in the sport’s surrender to the gambling-addiction economy.

Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred’s shock announcement that alleged game fixers “Shoeless” Joe Jackson and “the Hit King” Pete Rose would no longer be banned from the sport’s Hall of Fame was not about justice or closure. This is Manfred telling the high-minded baseball world that in the current political and economic climate, ethics are for suckers.

For those who don’t know the specifics, Joe Jackson hit .356 in his career—the fourth-highest batting average ever—and was banned for being a part of the Chicago “Black Sox” plot to fix the 1919 World Series. The charges beggared belief, since Jackson hit .375 in the postseason with zero errors. Jackson, who could neither read nor write, almost certainly took money, although it’s unclear if he understood the ramifications of what he was doing. Along with seven other Chicago White Sox teammates of varying innocence and guilt, Jackson saw his career destroyed. Baseball commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who had recently used the Sedition Act to sentence leading trade unionists to prison, banned the players from baseball, sending a message to the country that the honor of the sport could never be compromised.

As for Pete Rose, aka “Charlie Hustle,” no one in Major League Baseball has ever had more hits. He’s part of the history of the game whether people detest him or not. But fealty to the game’s history is not why Manfred is making this move. Some are positing that Donald Trump’s advocacy for Rose, his fellow alleged statutory rapist, is why this is happening. At the end of February, as ICE was abducting people from US streets, Trump found the time to tweet the following: “Over the next few weeks I will be signing a complete PARDON of Pete Rose, who shouldn’t have been gambling on baseball, but only bet on HIS TEAM WINNING.” Trump also apparently met with Manfred to facilitate this, part of his campaign to force every independent institution to wallow with him in his moral degeneracy.

Part of Trump’s reasoning is that Rose “only bet on his team winning.” Rose, from what we know, bet on his team as a manager, not a player. Shadowed by heavy debts and mobsters, Rose may have made pitchers stay on the mound longer or played people who were injured even if risking their long-term health. That’s why the “gambling on his team winning,” as if this were admirable, is a morally bereft argument. Trump sees nothing wrong with such managerial decisions, since it’s how he’s always treated his workers.

But please don’t believe that Trump is the reason Jackson and Rose are finally going to enter Cooperstown. Manfred may allow Trump to bask in the smell of his own influence, but this decision is rooted in something bigger: the sport’s surrender to the gambling-addiction economy, which could, in theory, be subject to federal or legal intervention.

Baseball has always taken pride in its history of patriotism and piety. Its early proponents were charged with spreading the sport in order to mend the United States and fortify the union after the Civil War. The first professional athletes to be feted at the White House were two baseball teams, guests of President Andrew Johnson in 1865. In 1889, Walt Whitman said, “Baseball is the hurrah game of the republic! [It] belongs as much…as our constitutions and laws. It is just as important in the sum total of our historic life.”

Hypocrisy, just like the country of its origin, is also baked into the game. It’s “the national pastime”—and it maintained a color line until 1947. Its Hall of Fame has shut out union trailblazers like legendary All-Star Curt Flood while honoring several rumored KKK members, including Rogers Hornsby. The MLB has enshrined alleged steroid users it likes and banned the ones it finds disagreeable.

But if there was one policy that would never be treated as ethically disposable, it was the league’s punishment for game fixing: banishment. The game had to be a stern exemplar of Christian probity even if the team owners were surely not. These war-profiteers and miscreants had stumbled upon virtue-branding: the profit potential of making clear to the public that this was not a low-born sport—like boxing or dog fighting—that lent itself to vice. Baseball would be a pastoral game on a verdant field that’s fit for the entire family.

This ironclad commandment around game fixing is now a casualty of Manfred’s reign, another example of his penchant for treating the game’s history as a nettlesome barrier to greater financial windfalls.

The Jackson and Rose decisions need to be seen in this context. Baseball has an aging fan base, and Manfred is trying to turn this around by catering to the hive of young, male addicts swarming around gambling apps. The sport that once suspended its greatest retired stars for shaking hands at a casino now has gambling partnerships with five different companies. The American Gaming Association is banking on MLB’s receiving $1.1 billion in betting profits this year. That’s four times the number in 2023.

Funding after-school leagues is not how Manfred sees growing the game. Instead, he is pursuing more and more partnerships that deliver gambling to kids without the brain development to handle the rush or the crash. The league used to want kids to want to become Major Leaguers. Now it wants them to steal their dad’s FanDuel code and become the class bookie. (I have a kid in high school; there is, in fact, competition over who gets to be the class bookie.) And if the addiction hotlines are ringing with youth gamblers, that’s not Manfred’s problem.

Manfred waited patiently and cruelly for the hard-living Rose to die, which occurred last September when Rose was 83, and only then did Manfred decide Rose could enter the Hall of Fame. Some of this was surely spite, as Rose has been a critic of league gambling hypocrisy, but it’s also because Rose in death can serve a new purpose: He can become a symbol that Major League Baseball isn’t your father’s stuffy sport as well as a symbol that gambling and addiction, far from being harmful, are really as American as apple pie. This has been a year when ethical guidelines once held as eternal have been shredded. MLB’s embrace of online betting signals the demise of another principle in a time of abject moral carnage.

More columns ⇒

Support the Work

Please consider making a donation to keep this site going.

Featured Videos

Dave on Democracy Now!