Mumia Abu-Jamal Speaks With the Clear Voice of a Free Man

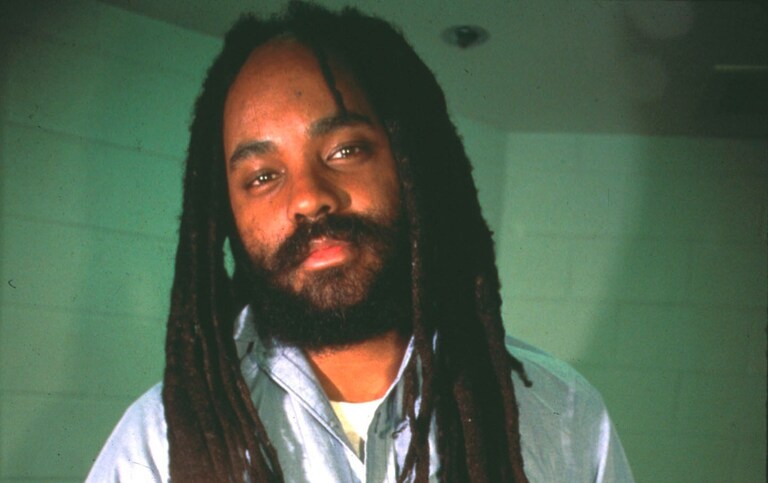

Mumia Abu-Jamal, seen here in a December 13, 1995, photo from prison, was convicted in 1982 of murdering a Philadelphia policeman. (Lisa Terry / Liaison Agency)

Incarcerated for 44 years, the political prisoner remains unbowed in the face of medical neglect.

The vibe was upbeat, or as upbeat as any meeting can be at the State Correctional Institution at Mahanoy in Pennsylvania. On October 16, alongside attorney Noel Hanrahan, I went to see the country’s best-known political prisoner, Mumia Abu-Jamal. A jury, who were told that Abdul-Jamal’s political writings could be used in determining guilt, sentenced the former Black Panther to death in 1982 for the murder of Daniel Faulkner, a Philadelphia police officer. It’s not just committed radical campaigners but organizations like Amnesty International that believe his trial and conviction were a sham and are calling for his case to be reopened. Now Abu-Jamal is on what he calls “slow-motion death row,” yet the state has been unable to silence his political voice or the movement to get him home after 44 years of incarceration.

For Abu-Jamal to meet us—and celebrate some good news—he has to endure a full-body cavity search. This is a precondition for all prisoners before and after visits. No exceptions. A 71-year-old Abu-Jamal is not exempt due to his age or stature as an “old head.”

The meeting room, where all the family, friends, and lawyers of these incarcerated men gather, resembles a high school cafeteria complete with vending machines against the walls. The one difference is that we have to sit around U-shaped tables that prevent prisoners from sitting directly next to their loved ones. There’s also an adjoining unmonitored play area for children with a collection of smudged and sticky toys.

In the visitor room, the guards keep one eye firmly on Abu-Jamal. Until recently, he could only pretend to stare back. Now he can. For nine months, Abu-Jamal, the author of 15 books, was blind. To restore his sight, he needed a five-second laser cataract surgery. Yet it took a legal battle and protests at the prison gates for him to receive the procedure. The problem wasn’t just being unable to read or see more than light colorful blobs. For his own physical safety, Abu-Jamal had to keep his blindness a secret. When I interviewed him earlier this year for Rolling Stone, I had to agree not to report on his lack of sight. Even for someone to whom many prisoners show great deference, he was vulnerable and could have become a target. So Abu-Jamal covered for it—walking direct lines in daily patterns: food, working out, and then listening (not watching) CSPAN in his cell. Again, this was for nine months. (Abu-Jamal would insist I write here that the criminal neglect of his health is a function of how all prisoners are treated.) Abu-Jamal needs follow-up care. He will have permanent vision loss without more treatments, and there is no guarantee he will receive them. But on this day, we celebrated that he can now get back to completing his PhD dissertation, start in on a stack of books, and just watch his own back.

That wasn’t the only reason for some good feelings. The previous night, Abu-Jamal spoke, without notice or prep, over the phone and into a mic at an event commemorating the recently departed revolutionary Assata Shakur, the former member of the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army who escaped a New Jersey prison to Cuba 46 years ago.

The evening’s host, Marc Lamont Hill, received a call from Abu-Jamal, a friend and coauthor of Hill’s, randomly during the program. “Marc saw the number and took the phone to the stage,” said WPFW program director, Katea Stitt who was on the scene, “We heard the prison operator connect the call, and Marc asked Mumia if he wanted to say a few words. Without a beat, Mumia said that not only was Assata Shakur born free. She died free. And he is saying this from behind bars with the clear voice of a free man; free because the state has not broken him. And this packed room of people were just clutching each other, and you heard sobbing.”

Abu-Jamal was pleased about his comments and the reception his words received. Even doing this has been a struggle; over the years, as his supporters and attorneys have fought to make sure his voice can be heard on calls and in print. It is great for the spirit to know you’re not forgotten.

I had also brought him a gift: my new favorite book, Black History Is For Everyone, by Brian Jones. Under the rules of the Pennsylvania prison system, I was permitted to show Abu-Jamal the book, talk about it with him and thumb through the pages, but he would not be allowed to take it back to his cell. I would have to send it later, through a “security processing center,” and the package would be vetted.

The book resonated with Abu-Jamal. One of Jones’s arguments is that the oft-heard line that “Black history is American history,” while true, is a little pat, because that social-patriotic sentiment cuts out people from Marcus Garvey to Fanny Lou Hamer to Malcolm X to Assata Shakur who, while they all have a distinctly Black American politics rooted in resistance to oppression, are internationalists to the core. They rejected “patriotism” on political grounds

Jones also makes the case that Black history has been and continues to be so relentlessly attacked and banned precisely because there is a liberatory power in a history that exposes the roots of why we have these savage inequalities of this country—inequalities exemplified by having the largest prison population in the world while its military cracks down against cities that buck the will of a grotesquely corrupt regime.

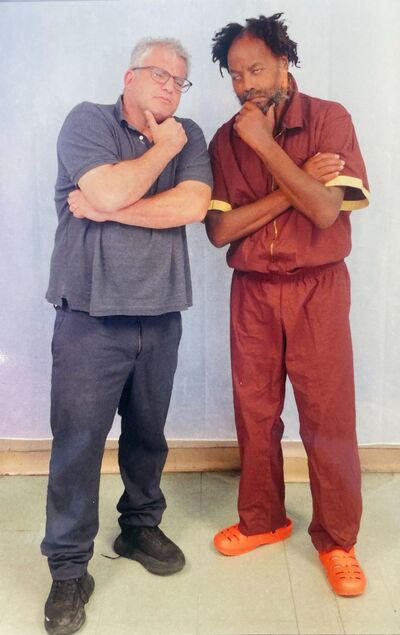

The prison, granting a right Abu-Jamal has fought for, then had a prison worker take our photos using the state equivalent of a Polaroid camera. In one picture, I happen to be holding Jones’s book. They confiscated that one. There are strict rules: no images, no T-shirts with slogans, no peace signs, no closed fist salutes—you can’t even make a heart shape with your hands, because it might be a gang sign.

Dave Zirin and Mumia Abu-Jamal. (Courtesy of Dave Zirin)

The prison guards looked exclusively white and were tatted from their arms to their neck. They came to work in Frackville, which once had coal-mining jobs and now has prison jobs. People whose parents may have worked in the mines with one another now are on opposite sides of the cage. It was hard not to think that if ever a community needed some liberatory history, it was Frackville, Pennsylvania. There is a rich tradition here of not settling for scraps. A 10-minute drive from the prison, there is even a statue commemorating the Molly Maguires, legendary 19th-century radical Irish laborers who agitated for better working conditions in the mines by any means necessary. History is everywhere, and Jones’s book makes the case that it needs to be taught.

After a farewell in front of the elevated guard dais, we were each handed two photos minus the confiscated one. Abu-Jamal, a grandfather with failing eyesight, had another body cavity search waiting for him on the other side of the metal doors.

After more than 40 years, legions of people still care about this man and his case. No matter what they do to break him down, he, as Stitt put it, “speaks with the clear voice of a free man.” I think he was excited to hear about Jones’s liberation history, because even behind bars, he is a part of that history. Abu-Jamal remains unbroken, and damn, does it piss the bastards off.

More columns ⇒

Support the Work

Please consider making a donation to keep this site going.

Featured Videos

Dave on Democracy Now!