Joe Frazier: The Real Rocky

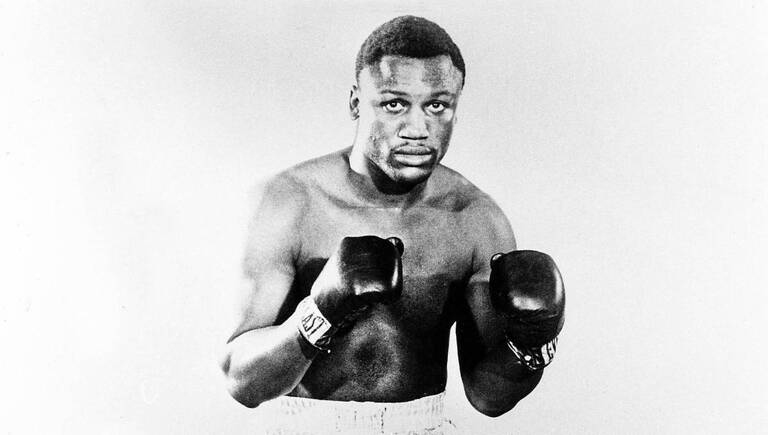

Joe Frazier in a studio portrait, circa 1971. (Unknown Photographer, Wikimedia Commons)

Every November 7th marks the anniversary of the death of former heavyweight boxing champion Joe Frazier and the more I read about his life, the more two things become obvious:

1) Joe Frazier is, without question, the real Rocky Balboa.

2) Joe Frazier is also the most unlikely sports icon in the history of this country. His biography is in fact so unbelievable, his stardom so unlikely, that it makes Rocky look like he was born with a damn silver spoon in his mouth.

Let me explain…

First, on the Rocky comparison. From the mean streets of Philly, to the humid gyms, to the freezing slaughterhouse, to the loping, punching style, to the family life, to the nemesis with the fast mouth, faster hands and wicked charisma, the fictional character could have easily been based on Frazier, with Apollo Creed playing the part of the de-politicized Muhammad Ali. Now, it's long been Hollywood lore that a boxer named Chuck Wepner -- who once gave Ali an unexpected hell of a fight -- was the direct inspiration. But Frazier's own iconic fights with Ali were a big influence and the fighter even has a cameo appearance in the first Rocky, almost as if he is haunting the proceedings.

But then the greatest insult of all: Philly, that great boxing, underdog, working class town, puts a statue up of their champion to represent their fighting spirit and it happens to be Rocky, not Frazier. Even worse, they place the statue by the very museum steps where Frazier ran and trained. (Yup, Frazier did that too.)

But as I stated earlier, Frazier's actual biography was even more unlikely than anything Hollywood could dream up.

Billy Joe Frazier was the youngest of 13 children growing up in Beaufort, South Carolina, a rural area so underdeveloped, the African American residents were given ownership and autonomy over the land -- in other words, it was such a perilous, unsettled place white landowners didn't even want it. Frazier's father had possession of his sprawling farm, giving Frazier a sense of pride denied to many African Americans in the pre-Civil Rights South. But the conditions were so bad that, out of Frazier's 12 brothers and sisters, three died as children. In fact, the infant mortality rate in Beaufort was 20% during that time, with most dying of malnutrition and disease. So the fact that Frazier even made it to adulthood was a minor miracle.

By age six [SIX!], Frazier was working 12 hours a day in his father's fields for one dollar a day. By seven, he was driving a pick-up truck and fixing motors on the farm. As a result of this hard labor, he was injured at a young age and couldn't extend his arm all the way, meaning he couldn't throw a real jab. His reach turned out to be only 71 inches, 12 inches less than Ali and Foreman.

The labors made Frazier strong as hell. But the food on the farm was always southern fried, so the he grew up slow and overweight. Frazier then married a woman named Florence, started a family and moved to Philadelphia with his wife and children to work in the Philly slaughterhouses for $105 a week, a job he would hold for the next several years.

Frazier began to show up at the 23rd Street Boxing Gym not because he had dreams of championships dancing in his head but because, as he put it, "I was so fat I couldn't get my pants on." Unlike so many fighters -- and athletes -- who are identified very quickly as possessing raw talent, Frazier was seen in the Philadelphia gyms by trainer Yank Durham as "just another fat kid who would quit after a couple of days." But Frazier caught the boxing bug. He kept returning at 9pm after working a full day to train. Durham saw someone who truly could not box -- Frazier was squat, slow and, as mentioned, couldn't even extend his arm to jab. But he could punch hard enough to "knock down walls" and had hands that were judged by Durham as having "welterweight speed."

So let us review: the man who would become the 1964 Olympic Gold Medalist and heavyweight champion was a short, slow, overweight dad who worked in the South Carolina fields at age six and in a Philly slaughterhouse when he was not training during the dead of night. Compare this to Ali, who was such an exemplar of speed and physical perfection, people took one look at him and were convinced he was destined for greatness. That is how athletics often works, particularly in poor black communities. Your destiny is often determined through the "eye test." Even Sonny Liston, born into similar poverty as Frazier, was such a fearsome boxer in prison, with his 93-inch reach, he was plucked out and placed in a ring.

Frazier failed every conceivable eye test, but he just kept training and winning with a ferocious tunnel vision that must have been utterly unparalleled.

Yet Frazier never received his due for his own amazingly evocative story. One reason for this, of course, is that Frazier was overshadowed by Ali. When you watch their fights today, with the old fashioned, distant camera angles, it is glaring how much Ali dominates the screen. He is tall. He is handsome. He stands straight with his hands down on his side. He is the center of every shot. Frazier, in contrast, is stooped, his head bunched down between his shoulders. It gives off the optical illusion of Ali being six inches to a foot taller than Frazier. It's also like watching a boxing match between Ichabod Crane and the Headless Horseman's kid brother.

Outside the ring, Ali similarly dominated. In the early 1970s, the champ, who was seen as a kind of Oracle, portrayed Frazier as a "sellout" and an "ugly, dumb Uncle Tom." This drove Frazier to tackle him on live television. While many may brush off Ali's taunts as trash talk, it's clear that some of the jibes got to him. The notion of being a sellout was especially unfair, since Frazier gave money to Ali when the latter was broke and banned from boxing. As for the war in Vietnam, Frazier said either that he had no opinion, or sometimes to goad Ali, that people should fight for their country. He also once said simply, "I don't think innocent people should die."

In other words, this was someone who really did not have any fixed opinion on matters of war and peace nor did he have any formal politics, which proved to be a detriment. Frazier lived in an era when being an athlete who wasn't political was viewed by young fans, particularly young African American fans, as a liability. Not taking a stand on the war in Vietnam and Civil Rights was seen as actually taking a stand, and by fighting Ali he was fighting, as sports sociologist Dr. Harry Edwards put it, "the Warrior Prince of the Black Athlete's Revolt." Young African American teenagers FROM PHILLY would show up to Frazier's gym and jeer him as he trained for his Ali fights. In any other era, Frazier might have been lionized as the most unlikely sports hero since an overweight orphan named George Herman Ruth picked up a bat. In the 1960s, however, this young man, this outsider, this one-in-a-trillion individual, became -- somehow -- a figure of the establishment.

Too many boxing writers believe that to praise Frazier you must also tear down Ali, or vice versa. The stories of both men are certainly seductive mirror images of one another, but they are also distinct. Frazier deserves to be remembered on his own terms: as one of the most driven and most unlikely sports icon to ever live, and yes, for the mere fact that he survived and even thrived when he was set up for failure.

These men, Frazier and Ali, Ali and Frazier, brought out the best and worst in each other, for the profit of a parasitic few and once for the prestige of a dictator in the Philippines. They also gave memories that shaped a generation. Ali now gets a respect best described as awe. Frazier's memory more than deserves the same.

More columns ⇒

Support the Work

Please consider making a donation to keep this site going.

Featured Videos

Dave on Democracy Now!